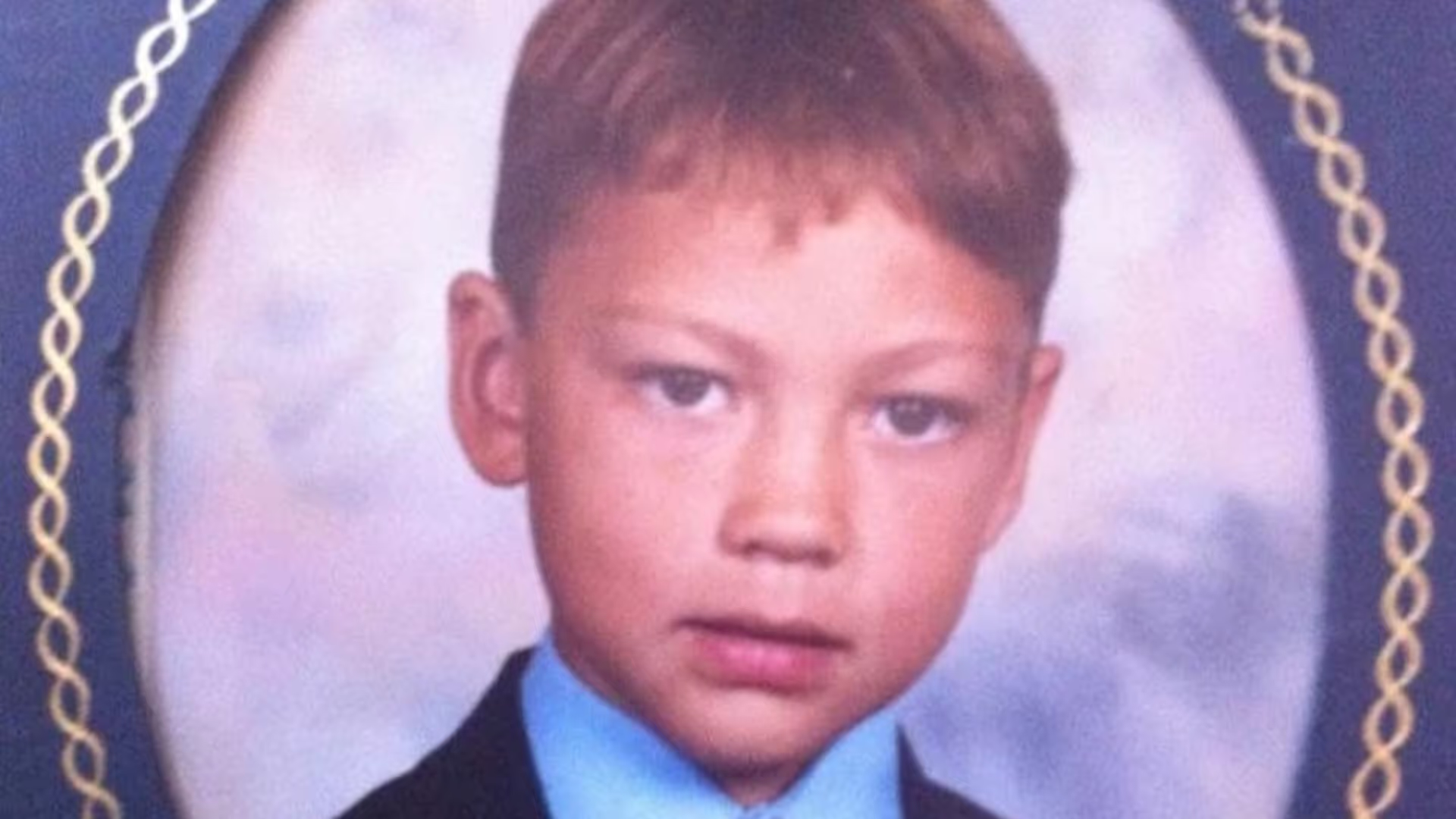

Tom's Story

Journalist, photographer and filmmaker, Tom de Souza (@storiesfromthescenicroute) reflects on his recovery from ice and gives an honest voice for Men's Health Month.

*Please note that this content discusses substances other than alcohol and comes with a trigger warning.

I injected ice for the first time at age fourteen. I came from a good home and a good family. The eldest of four kids, we spent the first eight years of my life in an affluent area of London, where I also attended a private school.

Our family began to fall apart when my dad lost his high-paying finance job in late 2002. It set in motion the great catastrophe of migration. My Australian parents decided now was time to return home, and back in Perth, Western Australia, Dad struggled to find work and Mum became the breadwinner. Money problems mounted, eroding the harmony and stability of our family unit.

Meanwhile, I struggled to find my feet in a new school, a new culture, a new world. I moved schools three times, eventually winning an academic scholarship to an elite private boy’s senior school. The scholarship helped to solve some of our parent’s financial problems, but I crumbled under the pressure of expectation and the school’s ruthless culture of conformity.

Uncomfortable in my own skin, I was determined to destroy myself.

You may be reading this and thinking, yeah, right. Spoiled, rich white kid rebels because he lost all the privilege he had grown entitled to. But the issues that afflicted me were the same that afflict all of us across Australia. Most men end up in prison or addicted to drugs because they are ill-equipped to deal with those issues.

I, like all young men, had to struggle to learn to love and accept who I was. To find a place in the world and discover joy and purpose and meaning in my life. To deal with pain and hardship in an insightful and constructive way. And as my family fell apart, I lacked the guidance and insight to find my way through these things, and slipped through the cracks.

Ironically, it was when I first became involved with the youth justice system that I discovered drugs. In 2008, I was busted by the police with a huge stash of white powder. It was only caffeine pills that my mum had found hidden in my bedroom, but when she asked me what they were I said nothing. I was angry and did not have the self-awareness to communicate how I felt. I punished the people around me to try to show them those feelings.

In reality, punished myself.

The police convinced my parents that a night in the cells of a juvenile remand centre would shock me into change. Despairing of options, they broken-heartedly agreed. In fact, juvenile detention had the complete opposite effect. It instilled in me a hatred of authority, told me that society rejected me, and forced me to adapt to a criminal world.

I found myself in the revolving door of the criminal justice system. I returned to juvie three times in the next three months, before I was bailed into a youth drug rehab. Here, I lived with a group of older boys and girls, most of them experienced drug users. They taught me more about ice and criminal behaviour than I ever could have learned otherwise. Drugs and crime were glamorised and I became enamoured with them. I went looking for them soon after getting out of drug rehab.

Not long after, my parents divorced.

My behaviour was both a symptom and a cause of the family breakdown but in my adolescence, I was at the centre of my own universe and I assumed responsibility. All at once I felt the guilt and anger and pain of my entire world being ripped apart, the sadistic pleasure of greater freedoms, and a longing for respite from the chaos the divorce might bring.

I understood none of these feelings at the time, and I sought to block out all of the feelings the only way I knew how.

Ice.

I found it through a veteran junkie named Mado. At 35-years-old, he was over 20 years my senior. Mado groomed me to inject drugs and schooled in me in ways to fund a prescient habit: drug dealing, stealing.

I looked up to Mado. He was the only kind of male role model I was permeable to. I was riddled with anger towards my father, and Mado curated a false sense of belonging and guidance. I was vulnerable to his influence. Especially while high on ice.

My descent into total addiction was rapid and all consuming. A few months after my first shot, I had a $400 per day habit. Ice vanished any sense of empathy and compassion in me, and I did anything I could to fund my habit. I stole from people I loved, I hurt people who tried to help me. I didn’t care for their pain or their hurt. All I cared about was that moment, that second, and what I could get into my lungs or up my arm.

All drug users arrive at a point where their drug use is no longer fun; it is a matter of compulsion and habit. Mine came as a rapid succession of catastrophic events, which also helped me to realise the need for change. The first was a psychotic episode: after ten days awake on ice, I flipped out and went chasing a non-existent figure about the streets with a meat cleaver. Fortunately, I was arrested before I could realise any harm. The second was a failed suicide attempt. The last, a murder committed by two of my closest friends.

Shortly after they were arrested and charged with murder, I was in the courtyard at school, awaiting an upcoming careers counselling session. It was a literal fork-in-the-road moment. The outcomes of each lay clearly ahead of me. Down one road was a life-sentence in prison. Down the other, the possibility of a future: an apprenticeship in cooking, or a career as a teacher, journalist, or writer. A multitude of choices and freedom.

Perhaps the most difficult part of giving up drugs is relearning how to live. Remaining sober is a question of willpower but starting all over again is a lonely and disconcerting business. You need new everything: new friends, new habits, new hobbies. For years, I found negotiating an overgrown, winding path between the two worlds: unwilling to turn back to the world of drugs but institutionalised and isolated from regular society.

After such an intoxicating emotional rollercoaster, it is also difficult to find joy in the simple pleasures of life. Studies show it can take the brain almost two years to recover and begin producing normal levels of dopamine after prolonged methamphetamine use. Surfing helped me immensely with this. It made me feel good and clean, and gave me a natural healthy substitute to ice.

I discovered a sense of purpose with some help from my grandfather, Ian, a renowned artist. I sought his counsel as I struggled to find my way. We cooked and played music together, and I saw the passion he derived from his art. For him, art was a way of life. He applied a creative way of thinking in everything in his life, from how he designed his house to how he cooked and worked and went about his daily schedule. He motivated in me a desire to discover my own sense of passion through work. I began to travel overseas on surf trips and discovered writing, photography, storytelling.

It has been almost nine years since I’ve touched ice now. I work as an independent journalist and writer, travelling and telling stories for various publications: The Australian, The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald. It has taken an enormous amount of work, failed relationships, tears, isolation, and hard-earned wisdom to arrive at this point today.

Drugs compound a problem but they are not the problem itself. Drugs are a response to a problem we do not know how to resolve. And to truly resolve a drug addiction, we must address it at its deepest and most painful roots. Many go through life and never do. Anyone who has the strength a willpower to walk away from drugs does so only some kind of higher purpose: be it God, work, a family, a passion. Or just life itself.

Words: Tom de Souza

Ready to get started?

.png)

.avif)